Before Paradise

- Luis José Mata

- 13 may 2021

- 12 Min. de lectura

Actualizado: 19 may 2021

Cuento "Antes del Paraíso" de Pedro Ugarte

Translated by Luis José Mata.

"I don't blame myself for not loving him enough.

I blame myself for not having understood him".

Jules Renard.

My father was a catholic who always went to mass. My mother was not going very much. That is not to say that she was not a catholic. Nor does it mean that she was. Well, I'm sure that just asking my mother about it would make her very nervous.

It was my father who kept that alive in our house. In a way, he was in charge. He put us to bed at night and prayed with us; he took us to mass on Sundays, and also, at Christmas, before dinner, he had us saying a prayer in front of the nativity scene figures. Yes, he took care. My mother limited to hear his voice, saying ("Let's pray"). She docilely followed him, with the inertia of those things done without any resistance and lack of conviction.

The personal God. That was the expression that Ramón had taught us in class; Ramón or, to put it better, the "father." Nowadays, priests seem young, foul-mouthed; they wear jackets, jeans, sports shoes. They speak of a personal God as if the alternative were an impersonal God. Precisely, nobody knows; no one knows what they pretend. They are so vague that they do not look like priests, but you find out what they are by accident, in the middle of the school term. When our adolescence arrived, those modernists priests taught us, religion class. They tried to look younger, as young as us. In class, they rushed the subject of religion with so many qualms, so much modesty, so much self-criticism, that they ended up, without us knowing very well how in the repetitive chant of a personal God. It was inevitable to conclude that this concept does not exist.

"Dad, I don't believe in a personal God."

A day arrived when I thought I should say that to my father, face to face. I went to the studio where he used to write, and I released the phrase, that phrase that almost resembled the words that Ramón used to say. I knew that if Ramón had heard me, he would practically have congratulated me, but I didn't care about the opinion of that priest in jeans: I cared about the thought of my father.

When I said the phrase, I thought he would slap me, insult me, or ground me. I had prepared myself for any of those things to happen. But everything that came out was much more effortless, surprisingly easy. My father looked at me carefully, examining each of my face's features, searching for himself deep down my eyes. Then, he hugged me. It seemed to me that, more than being scandalized, he was already waiting to hear something. Perhaps he had been preparing a long time ago; yes, maybe he had prepared that scene as much or more than me.

After hugging me, my father kissed me on the cheek. He told me to think whatever I wanted and that I have the right to believe what I want. He also said to me, "I would pray for you." From then on, he decided to go to mass every day. I knew him and knew why he did it. He was not joking when he said he would pray for me. Now he was going to mass every day to pray for me. My father was asking God to make me believe in Him again, in the personal God, the God of whom Ramón was speaking, and that, somehow, it was also my father's. He would never call Him a personal God. However, if he had met Ramón, he would have crossed his face for filling our heads with nonsense. My father kept his new practice of daily mass for a few weeks. Then he got tired and limited to church on Sundays, but he never asked me to go with him again.

My father and mother worked very hard, but they drank and drank at the end of the week until they lost consciousness. There no other way to say it. Sure enough, they would not have liked me to talk about this issue; it would seem unfair and unnecessary to them. But saying they drank too much was the truth or at least part of it.

Every day my father went to work at a college. On a suburban campus, he passed the whole day, tied to a job as an office clerk. But for many years, it never ceased to be temporary. I don't know if it scares him or not because sometimes he returned delighted and sometimes with a shadow of sadness that darkened his sloping forehead. By night, getting over the exhaustion that had left a long day's work, he cooked dinner for us, crossed some phrases with my mother, took us to sleep, and then he locked himself in his studio and began to write.

My mother went to college, a different one. She worked only in the mornings and passed the afternoons with our grandmother, many miles from home. Grandma had been bedridden for years, with that stubbornness of people who do not want to live but who seem willing never to die. My mother went back home after a long subway ride, and then, exhausted when it was dark, she tried to help us with the homework. I think my mother felt guilty about something. It took quite a bit for me to realize that all people feel guilty about something that only they know, or something they will never say to anyone, maybe not even to themselves.

Something was missing from my father and my mother. Perhaps a few things did not go right, or maybe went right, but not as good as that should be. Yes, during the week, we were an organized family. However, my parents changed their behavior on holiday days. They did not go out and began to drink very much. When we were minor, my sister and I played in our room. The hours went by, and nobody called for dinner. Suddenly we realized that it was late. We were hungry and did not know what to do. A corridor that looks like a tunnel scares us. At the other end, a point of light emerged from the room. It was a flickering and unreal light from the television, sending out imaginary ghosts along the dark house's corridor. Yes, those ghosts whisper with faint voices taken from old movies or forbidden nocturnal television channels. We called out loud to our parents, but they did not respond. After gathering courage, we set out in search of them. Then, my sister and I, holding hands, whimpering, crossed that endless corridor, full of black holes and ghosts. Finally, we found them —our parents— in the living room, each one lying on a couch, profoundly absent. They look silently lethargic.

When I got older, I concluded that falling asleep is the gentlest, most honorable way to end drunkenness. No, our parents never defaulted on their daily obligations. Still, I think they achieved that thanks to the expectation that, whenever the week ended, a quiet domestic refuge awaits them, a place to get methodically, deliberately drunk, until they forget everything. They never broke up, and they never called each other loud names, never did one of them slam a door. They didn't hit or scratch each other. Of course, they didn't like each other. I think they had learned to hurt themselves in silence.

My father has obsessions. If you were going to put in a garbage bag an empty container, you should first fill it with more trash to make fair use of the space. My mother used to say that this was ridiculous. Sometimes they argued over things like using the garbage bags, the thermostat level, the oven, or microwave functions. My father insists on top up the containers before throwing them away. My mother insisted on throwing them out even if they were almost empty. Nobody raised their voices, but in those moments, the kitchen's atmosphere became tremulous, convulsive, electrifying. I would have loved to throw the container away, empty and full at the same time.

My father wrote at night, but he dragged an invisible burden that prevented him from becoming a writer. No, he was not a writer, although, at home, he spent most of his time reading and writing. He busied himself, constructing buildings of words or visiting buildings that others had built a few years before him, or many centuries before him.

When I became a teenager, I began to be curious about my father's long seclusions. Sometimes I would walk into his office and see him sitting with his back to the door, pounding furiously on the computer keyboard. Someone could imagine that he had aired something important there because of the conviction with which my father typed.

One day he notices me. He thought that someone had entered his little kingdom of words. He stopped typing and, without turning around, knowing I was there, my father said: “I've been doing this for thirty years, Jorge. I always write the same things, they are still the same stories, and I always write them in the same way." He keeps talking: "There was a time when I believed that so much work would do something good, but nothing ever happened. Hopefully, I have twenty more years to write the same things, write the same stories, write them in the same way." He keeps saying: "There is no more fear or hope: I know that nothing good will happen, but at least I also know that nothing wrong will happen by writing them."

Yes, my father has obsessions. So as I could not eat in his office, and even less at his working table, near the computer keyboard, that was what made him angry. There could be landslides, floods, tidal waves, epidemics on the planet, but if my father saw a single crumb of bread on his table, he was able to crucify me with his eyes and punish me later. When he was at work, I used his computer to do my homework or play games, and I also had a picnic at the table. And although afterward, I tried, with great care, to clean everything, there was always some telltale crumb, a microscopic crump, invisible, that I had not detected in its slight softness. Still, my father later founded it when he perceived a small and hardened ball under his forearm.

And he was angry.

My father and mother never went to bed together. Different clocks fixed their lives. When one did something, the other reacted out of time.

On weekdays, my father wrote at dawn, but what could he do? It was the moment that he allowed life to take care of his things. And at the same time, my mother was falling asleep in the living room, cradled by the television narcotic rumor, an artifact crammed with the same and predictable products: soap operas, TV movies, telemarkets. When it was too late, she would wake up and stumble down the hall to the bedroom.

My father also read on his nightly vigils, but he used to be so tired that he didn't remember anything the next day. I would never have suspected it until once when I was fourteen or fifteen years old, he told me about that intimate tragedy.

"I don't remember anything; you know Jorge? It isn't perfect. Yesterday I read for more than an hour, and I don't remember anything", said my father.

I felt sorry for him, that sort of pain that children will feel like the puncture of sharp steel when years passed, and their parents' defeats become impossible to hide. When he said that, his voice came out somewhat cracked, holding a tide of liquid in his throat that was struggling to leave. Years later, when I was coming home at dawn, I would find my father asleep on the couch, with a book open on his chest, and I would imagine him in the coming hours, trying to read, blinking, nodding, fighting against the dream, against time, against everything.

My mother resembled the stately hostesses of another time: she liked to see her house full of people. She treated dozens of guests with exquisite delicacies. Several times a year, she organized spectacular dinners and began to prepare days in advance, and on which she concentrated enormous efforts. I knew that night my parents would drink as usual, but at least they would do it in the company of more people, which would erase the sordidness of the other times. Before shopping at the supermarket and the butcher shop or browsing the internet in search of fantastic recipes: she took on the challenge of overcoming herself and once again surprising old guests with new dishes.

My father accepted these gatherings because the guests were often his friends. When they arrived, the house experienced a detonation of loud voices, compulsive laughter, spasmodic reactions in chains and jokes that they had doubtless been repeating for twenty or thirty years, while reliving, in endless talks, stories told, heard, applauded, cheered countless times. Throughout the years, stories that rescued old adventures: that drunkenness, those messes, those lost girlfriends, that dead friend. Then there was silence.

The dinners at my parents' house were expeditions beyond the mountains, a trip to distant continents, a long stain into the past. On the sofas, the evening prolonged with glasses filled and emptied at the speed of vertigo. At the same time, they continued talking and drifted, now, to recurrent discussions of politics or sex, history or religion. The meetings ended, out of sheer exhaustion, at four or five in the morning. The atmosphere relaxed; someone made a negative comment; someone mentioned that dead friend. Then again, there was silence.

And everyone, exhausted, went home.

My father has obsessions. On Friday afternoon, when he considered that he had already accomplished his hard work and family duties, he would go down to the supermarket and buy alcohol for the weekend. He purchased a lot of alcoholic drinks in large quantities. He took care that there was no season of the day without its corresponding dose: vermouth for the morning, wine for lunch, after-dinner liquor, more wine for dinner, rum and gin for the evening.

He came from the supermarket with many things, his colossal cargo. He always accompanied him with something else, some insignificant product that he had bought invaded by guilt, in the supermarket queue that served to certify his status as a family father. Then accompany that glass exhibition of different colors with some nutritional addition. So he could bring a half dozen apples, or a packet of spaghetti, or a few yogurts.

"You are ashamed," my mother would say to him, with more sarcasm than she should, while he silently took out of the bags all the bottles that together they would angrily drink later.

My parents have been dead for years. It is difficult for me to recall the color of his gaze, his way of moving or calling me. Some people claim to remember the past and those who were stranded in it forever. It doesn't seem so easy to me. The faces of my parents are gradually disfiguring. If they are useful for anything, the photographs should be to fix the image of the people you love and who are no longer here. Still, there is a betrayal nesting in them, as if they were a documentary crutch, a bureaucratic instrument. My father would also say that to know something about him, any of his stories would be more important than a photograph, a recording, or a film. I make an effort to preserve my parents' memory, in the light of the photos, because that memory, however vague, does belong to me. They live in my memory the same way they live in the blood that I owe them. My sister and I are her true legacy. The most real thing that exists of them is not those photos, not even all those stories that my father built, tirelessly, at dawn, until his strength failed him: what remains of them are my sister and me.

Now, I have learned to love them as much as they loved me. Because this has to do with one of my father's favorite phrases: when I disobeyed him, or when I did something he did not like, he always resorted to the same sentence, that phrase of a Christian that first seeks to enlarge the guilt and then chase after the redemption. He usually said: "When I die, only when I die, Jorge, you will love me as much as I love you now." My father's phrase was that moving. Or so cool, who knows.

I hope there is someplace where my father and mother continue to drink together, a place where they can love each other with a little less awkwardness. I hope that right now, they are heading, kneeling, towards some celestial thalamus where they can get rid of the fatigue they carried throughout their lives. I hope they reproduce the admirable, peaceful, and courteous drinking way, which never disturbs the divine order.

"Men reject God, resorting to rational arguments," my father used to say. "But what animates them is a vulgar superstition, that is to say, the existence of a better place seems impossible because that would be too good," he ended up saying. But, my father always added, "They think that there can be nothing better than this misery" and kept saying, "You see? They say they are rational, but they are only pessimistic."

However, one day when I had already decided to speak with him as equals when I dared to contradict his ingenious paradoxes and said, “If it is that way, if you believe so firmly, why do you drink like that?”

Children carry a demanding portion of their parents in their consciousness, and parents assume, where nothing happens, a similar burden. Parents support their children with one invisible hand, while with the other, they help themselves, and that double task, so painful, occupies them until they die. But there is a moment when one and the other's identity is confused, a moment when roles change or perhaps overlap. I am writing to record how much I loved and still love them, record that I knew of their weaknesses and failures, and document that they, why hide it? They knew it too.

Pedro Ugarte es un maravilloso escritor de cuentos. Ganador de muchos premios literarios en España. Mi intención es dejar en inglés este hermoso cuento. Me alegro de haberlo logrado con el permiso de Pedro Ugarte.

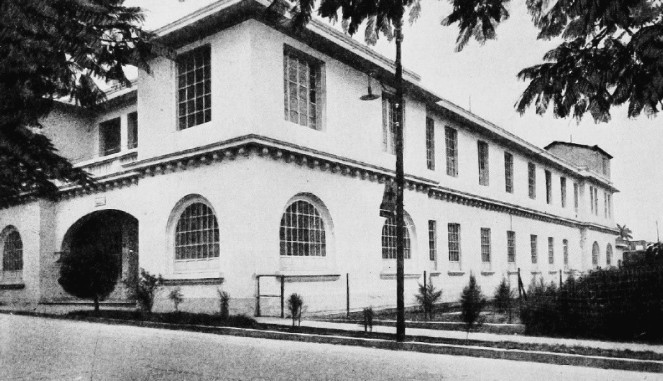

Portada de Antes del Paraíso

Comentarios